Architecture

Arts

Antiques

Design

Gifts

Home Decor

Interior Design

Green

Food&Wine

Rooms

Textile

Travel

PERIOD: Art Nouveau

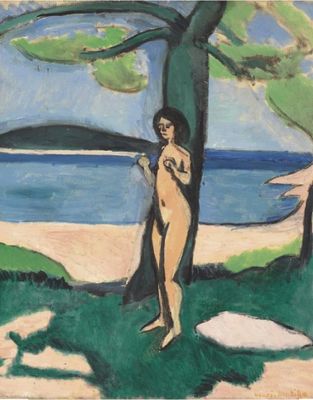

Nu au bord de la mer signé 'Henri Matisse' (en bas à droite); signé, daté et inscrit 'Ce tableau a été peint à Cavallière [sic] (Var) en 1908 [sic]. Henri Matisse Nice, 25 avril 1935' (au revers) huile sur toile 61.2 x 50 cm. (24 1/8 x 19¾ in.) Peint à Cavalière, 1909This seemingly innocuous painting of a girl on a sunny beach beneath a shady tree was in its day a deeply subversive image. Nu au bord de la mer is what the collector Marcel Sembat (who was one of the first people to see it) called "an egg"1. He meant that it contained in embryonic form the makings of a raw new visual language that would change for ever the way people looked at the world around them. To most of Matisse's contemporaries, the canvas was a jumble of coarse black brushstrokes outlining meaningless patches of flat colour, the kind of painting that threatened to overthrow established moral as well as pictorial values. This particular Nu belongs to a series of radical experiments expressly designed to clear the way for the two great canvases, La Danse I (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) and La Musique (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo), which Matisse started working on immediately afterwards. La Danse (fig.1), which seemed grotesque, barbaric, even obscene on its first showing to the Parisian artworld in 1910, went on to become one of the emblematic works of twentieth century Modernism. The first version - Danse I - hung from the 1930s onwards in the marble entrance hall of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Danse II (Hermitage Museum, Saint-Petersbourg) occupied pride of place meanwhile in Moscow's Museum of Modern Western Art (where it was used as a teaching tool to demonstrate to the Soviet public the decadence and corruption of the West). Nu au bord de la mer was painted on a barren headland outside the tiny fishing village of Cavallière in the summer of 1909 (the painter, whose memory was notoriously unreliable on dates, was one year out when he finally signed the back of the canvas quarter of a century later). Matisse's summer at Cavallière marked the final stages of a rigorous training programme which he had laid down for himself in early February, when the Russian collector, Sergei Shchukin, commissioned two wall paintings for his house in Moscow. The subject they agreed upon was La Dance. Matisse saw the commission as a public manifesto, an ambitious attempt to produce on a grand scale a new art for the new century. In it he would combine the unmodulated colour that had exploded on his canvases in the 1905 Fauve summer with the sense of overall design that had increasingly preoccupied him ever since a first visit to Italy in 1907. He had responded with particular intensity to the radiant lucidity of early Florentine painters, and to the emotional power of Giotto's frescoes in Arena chapel at Padua, where the interaction between line and colour possessed the force of a revelation for Matisse2. Nu au bord de la mer looks back to Botticelli's luminous Birth of Venus (fig. 2) with its structural central figure, its shady grove of evergreens and its triple bands of colour representing earth, water and sky. The series of nudes Matisse painted at Cavallière derived directly from a pair of canvases produced in 1907, immediately after his return from Italy. In Le Luxe I (fig. 3) and Le Luxe II (The Royal Museum of Fine Art, Copenhague), he transposed and telescoped the central and righthand sections of Botticelli's canvas, appropriating its chromatic banding, its wedge-shaped headlands and its tall long-legged nude with her attendants bringing flowers and drapery. Even the rumpled beach towel on which Matisse's modern Venus stands makes a flat white patch of paint, curved and ridged like Botticelli's seashell. Two years later the echoes are at once more direct, and more thoroughly absorbed, in Nu au bord de la mer. Like Botticelli, Matisse divides his canvas horizontally by colour, and vertically by the columnar upright of the nude. Earth, sea and sky make flat parallel strips of green, pink and four different blues with the same spurs of land lined up one above another on the right just as in Botticelli's canvas. Matisse's model has been more or less reduced to trunk and limbs, her narrow hipless breastless body accentuated by the tubular bole of the pine tree at her back. As so often in this transitional period, the painter turned to the art of the past to find the impetus that would launch him into the unknown territory of the future. In a second variation on the same theme, Nu, paysage ensoleillé3, the human figure is almost entirely assimilated within the patterned play of straight dark tree trunks and irregular rounded areas of pale soil. This time Matisse posed his model in a pine grove at the top of the beach: "she stood in grey shadow against green foliage, making a patch of flat orange-pink hardly darker than the sandy sunlit ground (with an emerald patch between her thighs)".4 A third variation, Nu assis (Musée de Grenoble), conducts a dialogue not so much with Botticelli as with a canvas by Gauguin that had lodged itself at the back of Matisse's mind a decade earlier in Ambrose Vollard's shop on the rue Lafitte ("one of the finest Gauguins I've ever seen: a big nude, a magnificent Tahitian, beside the sea"5). The painter traps the vibrant light, heat and colour of a Mediterranean summer in wavy strips and splashes of blue, green, deep pink and indigo. Nu assis was the "egg" that mystified Sembat, "something gripping, unheard-of, frighteningly new: something that very nearly frightened its maker himself." Sembat claimed afterwards that he had screamed out loud when he first saw it on 30 October 1909. He bought the painting a week later, explaining that it took time to sort out visual sensations that had seemed initially harsh and discordant, like modern music. "You see, I wasn't just trying to paint a woman," Matisse told him. "I wanted to paint my overall impression of the south".6 Matisse rarely went even as far as this towards defining the role of women in his work, although he did admit long afterwards to his son Pierre that he could not endure the ordeal of painting without the consoling human presence of a model7. In 1909, she was a professional called Loulou Brouty, a small compact Parisienne with a muscular body, dark hair and and neat cat like features who had already posed in the studio for La dame en vert and Nu à l'écharpe blanche. Matisse brought her with him to the south because he knew only too well that it would be impossible to hire a model, let alone persuade her to take off her clothes, in a place like Cavallière, still even more cut off from the outside world than the villages of Collioure and Saint-Tropez where he had worked in previous summers. Extreme isolation was the prime attraction of this bare scrubby foreshore with little shade, no fresh greenery and nothing picturesque about it, where the painter planned to stage a final crucial confrontation with his model in the run-up to La Danse

PRIX: $7500000